Booklice Bugs in Grain Stores. Should you Fumigate?

Sunday 24th November 2019

Booklice bugs in the grain- why you might not need a fumigation

Ok, so you’ve looked in your store. Everything was fine a couple of weeks ago. Now all of a sudden, you see that there are hundreds, if not thousands of tiny winged insects all over the surface of the grain. They are crawling up the walls and over the tunnel. Curiously they seem to congregate in the shadows. What are these creatures and how have they slipped your attention, when there are just so many of them?!

The humble booklice or psocid is an insect that is often found in grain. By our data, we find it in 83% of grain stores. If you are talking malting barley stores, I would suggest that they occur in even more than that.

The Dealey Fumigation team are always being called out to look at psocids, but we always tell our lovely farmers not to panic, not to order fumigation and to save their money. Let me tell you a bit more about psocids so you can understand why.

There are 5000 odd species of psocids, 400 of which can be found in grain. It is one of those cases where they are identifying new species all the time. I would suggest that, if you want to see your name in lights, you could scoop up those little critters and send them off to the Linnean Society. They might name it Psocoptera Dave, or something of that ilk.

The name psocid is an abbreviation their proper name is Psocoptera. The name Psocoptera is Greek; it means ‘Grinding Wing’ which is a tad bizarre. The grinding part of the name refers to their mouthparts which are shaped much like a pestle and mortar. So, they don’t really chew their food; it’s more of a grinding motion.

So, what are they grinding? What does a booklouse eat? Well, they haven’t been given the name booklice by hanging out in grain stores, that much is clear. In cold and damp libraries in old houses, there is plenty of scope for mesophilic fungus growth; you have a dark, damp cold and an organic substrate (the books). The mould that then grows on the books is ideal fodder for booklice.

Coincidently your grain stores have the same conditions.

Cold

Dark

Organic substrate

Damp?

But really what is so damp when you store at 15% or lower?

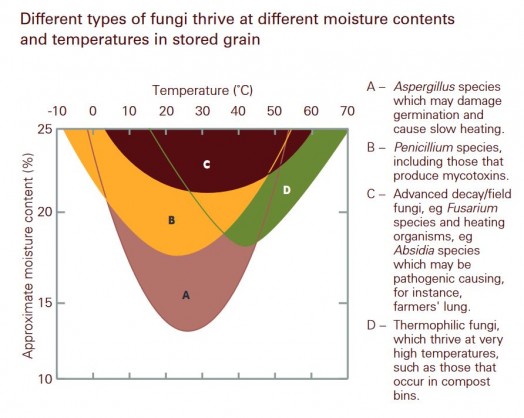

Consult the chart to the right (it's below if you are on a mobile, sorry). From the CSL studies done a couple of decades ago at York, the boffins came up with this handy storage graph. As you can see, you might still get mould growth storing grain below 15% if the temperature is right. Pesky Aspergillus.

Secondly, we also see much greater numbers of booklice bugs in grain (in the northern hemisphere) after Christmas. This is because it is around this period that the grains in store begin their natural process of hygroscopy.

Some people forget that grains are still living seeds, and they have a biological clock, just like all other living things. During winter, in the wild, they would take on the water ready for spring germination. And the grain in your stores is no different. The top 12” or so will sometimes jump up as much as one or two percentage points during this period as they are the ones exposed to the atmospheric moisture of the store. The overall effect of this on your stored crop is almost nothing because it only affects the top layer with the lower grain retaining its moisture percentage quite well.

So, the mould that then grows on your grain becomes the ideal feeding ground for psocids. But why so many?

Here comes the science bit.

Booklice can breed by parthenogenesis. This means that when a female hatches from a fertilised egg, she can lay eggs herself that are already viable for hatching. So there doesn’t need to be any reproducing going on for the second step of population growth to happen. All of the freshly hatched females are genetically identical to their mothers. This makes scientists very excited about booklice- because varied genetic testing can be applied to a series of genetically identical insects—crazy fun scientists.

Parthenogenesis might sound strange to us, but this “virgin birth” is quite common in nature. There are species of worms, snails, bees, crayfish, lizards and fish that can reproduce in this way. The most famous examples are probably Komodo Dragons and Hammerhead sharks. Scientists have even observed virgin birth in mammals, with one recorded incidence in lab mice. People got very excited about this because of the implications for Christian and ancient mythology. But sadly, the scientists didn’t observe this naturally, rather with some, fairly severe, coaxing and prodding of the poor lab mouse’s genetics.

But back to our psocids.

Because of their ‘double step’ in population growth and the relatively high number of eggs each female can lay (up to 100 pre-fertilised offspring, so potentially 10,000 adult offspring from one fully loaded female), the population can get out of hand quickly. So, things look much worse than they really are. The great numbers have very little consequence for the quality of the stored grain because these are secondary grain pests remember, so they eat the fungus that grows on grain rather than the grain itself.

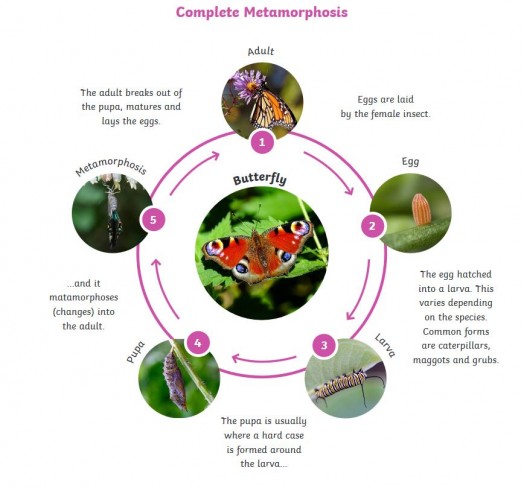

The real problem comes from their old-school life cycle. Most of the other insect grain pests you will encounter will go through a life cycle of complete metamorphosis; they go from egg to larva to pupa to adult. Grain weevil, rust-red flour beetle, sawtooth grain beetle etc. are all like this, they follow the life stages of a more recently evolved insect like a butterfly goes from egg caterpillar to chrysalis to adult.

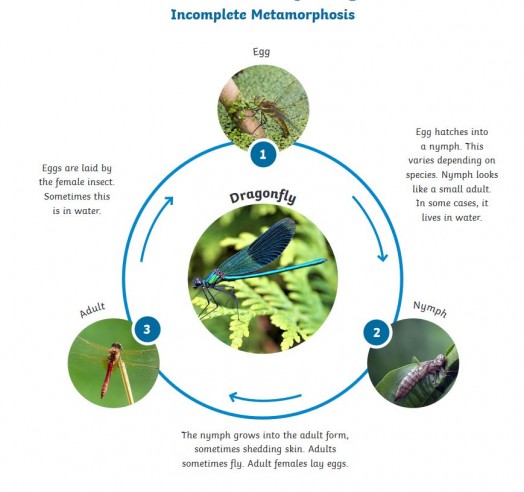

Booklice, however, go through an incomplete metamorphosis as they grow into adults. This is where they hatch from the eggs fully formed as nymphs and then go through several growing stages, each stage involving moulting as they outgrow their exoskeletons. It is this shedding of skin that causes the problem. They leave all sorts of skin casts in the grain, which can lead to some serious allergic reactions in some sensitive individuals. There have even been some suggestions of anaphylactic shock being brought on by exposure to booklice. Whether this is true or not, I can tell you that I have worked a lot with psocids in the past and they have always made me sneeze like billy-o and given me a rash on my hands where I come into contact with them.

Some weigh-bridges in the UK have started rejecting loads because of the presence of booklice, and they may be right to do so. The contracts of sale for these commodities often have the phrase “free from live infestation” in the small print, so a rejection on these terms is fair enough. Some have pointed to psocids being evidence of poor storage conditions. While this might be true in some cases, you can see from the above reasoning that psocids can be present in pretty much any shipment of stored grain.

There is one more thing to mention about booklice in grain. I am about to share a ‘bugs in grain’ secret with you here as a little reward for coming this far through the article. If you put your finger on an insect that you find in the grain and it gets up and walks off, then it is likely you have yourself a primary grain pest, something grain-injurious that needs fumigating.

However, if you put your finger on a secondary pest, it is likely, they will easily crush into nothingness. This will indicate that, as soon as you begin moving the grain, the bugs will die out from the natural abrasion of the grains rubbing together.

So, if you have a secondary pest like psocids throughout your grain store, the best thing to do is to move the grain about a bit, especially if you are storing over a year or into the late spring, moving the grain around in December or January always does it a world of good.

If the grain is in a bin or silo then a simple transfer or re-stir will do the trick, with 85% of insects killed in this way (ALWAYS CHECK YOUR AUGERS AND ELEVATORS FOR OTHER INFESTATIONS BEFORE DOING THIS!). If you are loading a lorry and you know you have had an issue in the year, then picking up a bucketful, dropping it back onto the heap and then picking it up again will work well. This is what our GrainCare guys call “the double movement.”

If you want to talk to us about Dealey GrainCare, please feel free to get in touch. We have banks of knowledge about each pest species which are equal to the above and there is so much more I could have included in this article, but I didn’t want to bore you. If you engage one of our GrainCare technicians, then they will be able to use that knowledge as power for their advice to you to get the best possible storage conditions for your product.